My nearly undetectable Stockfish cheat-bot played over 1,000 (up to) GM-level blitz+bullet games on Chess.com completely autonomously

I wrote a bot to play 1,200 games on Chess.com at up to 2800 level (top 1000 player in the world) totally autonomously and mostly undetectable to Chess.com’s anti-cheat.

The bot played over 1,000 blitz games up to 24 hours a day with no human input, only Stockfish and algorithmically selected moves, for several months (on and off). And it would have likely continued on indefinitely had I not made some inadvertent changes to the bot’s code. I didn’t expect this to work, given how little time & forethought I put into this, not to mention my inexperience and lack of expertise with chess engines.

Table of Contents:

Why even do this?

Everyone who plays on Chess.com is aware that the cheating problem is out of control and has been since before even Hans Niemann’s scandal rose to prominence in 2022. This is partly due to just how inherently difficult cheat detection is in online chess. Given only a sequence of moves and their timings, it’s pretty difficult to determine if and how an engine was exactly used. As players become more skilled, they need less and less help from the engine to dominate games. Like Magnus Carlsen said, if he started cheating, he would be virtually unbeatable and uncatchable by anyone.

Chess.com has realized this problem (somewhat) and has been pouring money out the fucking wazoo to try and fix it with a team of statisticians and data scientists. That said, their results are kind of pathetic even from an algorithmic perspective, even when applied to millions of games being played every day. That’s especially true because the VAST majority of cheaters in online chess are EXTREMELY unsophisticated and they should be (hypothetically) caught pretty easily. And many of them are. But not enough. Not nearly enough. I mean Chess.com is a fucking $500M-1B company. Aside from servers and sponsorships, where the actual motherloving fuck is that money going?

JackSark made an outstanding video about a year ago which estimated (with data!) around 1 in 3 Rapid players on Chess.com (2300 Elo pool) are using at engine at least some of the time. Not only that, but Chess.com only catches 33% of them. And among 100 opponents, he found just over 11% of them were banned by Chess.com. That tells us two things: there’s an absolute shitload of cheaters for sure (11% verified caught is, like, a lot) and there’s likely (but not guaranteed) an absolute fuckload more who go undetected, at least for a little while.

Regardless, the cheating landscape on chess.com looks something like this:

- Ragers make a new account, run it up to like 2500 Elo, and get banned for obvious cheating in like 20 games.

- Low level closet cheaters, typically 800-1500 Elo, cheat with some regularity and are banned with some regularity.

- Higher level closet cheaters are relatively common yet more difficult to catch.

In all of these brackets, there is a human in the loop interacting with the engine. And for the closet cheaters, they are not cheating nearly every move, maybe one out of every 10 or 20. IMO, it’s kind of a sad and boring activity to be cheating with a human in the loop, a scared little kiddo timidly playing the occasional engine line to eek out 8 more Elo in the advanced-intermediate range.

An autonomous cheatbot

I got interested in taking the idea of cheating to it’s extreme. What if we take the human out of that loop, and play literally every goddamn move from an engine algorithm? Being in the chess world for a few years got me thinking about what would happen if someone just put a little thought into a cheating strategy that has a little sophistication. And to employ this strategy in short time-control games like Blitz and Bullet where the suspicion of cheating is generally lower than in Rapid. What if we could make an undetectable cheat engine that could play entirely by itself? An bot like that could play thousands of games in any time control and could rise the ranks to be potentially the highest-rated account in the world (LOL).

It’s worth saying that on my actual account I have never played a single move from an engine. I don’t have a moral slant or honor, per say. I just don’t find it fun. The whole point of human chess for me is a personal challenge in playing a game.

Also, none of this is to say I don’t like Chess.com either. I like the game in general and actually think, for the most part, Chess.com’s platform is pretty outstanding at least in terms of gameplay and UI.

I decided to make this bot mostly as a programming challenge for curiosity’s sake. I am not an expert in chess engines. I am not an expert chess player. I have no inside knowledge of Chess.com’s fair play algorithm. I am not particularly well read on chess engine theory. I’m just a random intermediate player and programmer that thinks an algorithm + Stockfish can outwit cheat detection algorithms over a long period of time.

On first attempt, the bot managed to do this, at least for a few months.

So, reasons in a nutshell

- Weekend personal programming project for funsies

- To demonstrate that Chess.com anticheat cannot easily stop a shitty bot literally only playing moves from Stockfish

- To cause a microscopic amount of mayhem

Keep in mind I am aware this is not a super noble or impressive pursuit. I made this solely as an offtime funsies project to see what I could do.

Chess.com’s cheating detection methods

Common knowledge is that Chess.com has relatively good (lol) anti-cheat able to catch a cheater from a handful of suspicious moves. “Good”, in this case, is relative, because automated systems for detecting chess cheating are woefully unreliable and most cheaters are unskilled rage-cheater idiots.

Broadly, anti-cheats work by determining how much a player’s moves correlate with some number of top lines (series of moves, AKA “variation”) from the engine.

In reality, the cheat detection algorithm is a closely guarded secret, and revealing it to the public would expose strategies on how to circumvent it. Similar to revealing secrets on military countermeasures, Chess.com has determined they are better left guarded. It is my opinion that Chess.com actually employs a multi-dimensional arsenal of anti-cheat strategies including inputs from:

- Move correlation with the top lines of engines at various strengths/depths. Moron cheaters will literally just play the top line of the engine every move: they are easily caught. Slightly more sophisticated cheaters will choose among the top lines of the engine to stay within a favorable evaluation (meaning the engine determines they are winning). Danny Rensch explains a bit in this Twitch clip.

- Expected average top line engine correlation vs. actual correlation for their Elo. We’d expect a high Elo player to have higher engine correlation or CAPS (computer aggregated precision score), a 0-100 range measure of player’s move “accuracy”, than a low Elo player. Chess.com denies they use CAPS score for determining fair play violations (claiming they have much more effective tools) but I believe they use metrics very similar to CAPS at higher engine depth as one of many inputs to their fair play detection.

- Machine learning algorithm (unlikely): Having some neural net learn the likelihood of series of moves given skill level and board state, such as Maia, an attention-based NN trained on millions of games. The NN can then correlate the likelihood of players’ moves given a certain position and their skill levels much like a human GM can pretty well predict low-level cheating behavior. A low-elo player finding an advanced sequence of moves might have a likelihood of 1%, but a similar behavior over 10 games might narrow in on cheating with much higher certainty .

- Win rate per time (, unlikely): A player who rapidly starts beating players they have historically been stuck against might trigger an in-depth review.

- Move timings: cheaters typically are stupid and play high-accuracy, complex moves such as a 6-move tactical sacrifice with the same timing as obvious moves such as queen recaptures, ladder mates, or mate-in-one. Most cheaters are extremely unskilled players and aren’t good enough to make obvious moves on their own,. They have to spend a second or two to look at another screen (running their engine) to input the opponent move, get their next move from the engine, and then play it. If all the moves are 1-3 seconds, it’s pretty likely they are cheating.

- Player reports and account age: Chess.com’s

reportbutton probably does nothing 95% of the time, but once you rack up enough reports from players it is likely you’ll trigger an in-depth review. New accounts are much more likely to incur more scrutiny.

- Mouse movements/tracking (maybe): Tracking mouse movements might alert them to player’s using automated softwares or browser plugins for cheating. Calls to the browser to determine whether a player is tabbed in/out and other browser configuration can also be used to arouse suspicion of cheating.

In most cases, I believe they run some sort of low-fidelity anticheat after every game. If your account triggers enough red flags, they send you to the gulag for an in-depth review, where they churn some real compute with one or more of the above methods to determine whether you’re a dirty fucking cheater or just a lucky bastard.

But there’s only so much one can do with an automated anti-cheat.

Each and every one of these detection methods is circumventable. Mouse movements can be simulated with software to mimic humans. Move timings can be artificially inflated or changed to reflect human behavior. Improvement can be made slow and steady. And most importantly, engine correlation can be suppressed while doing just enough to win more games than you lose while staying far-the-fuck-away from 90%+ accuracy games, even against highly skilled opponents with >2200 Elo.

Chess.com claims they have a team of statisticians, data scientists, and wizards working full time on their fair play algorithm. But here I’ll show how their anticheat can be circumvented easily with extremely janky coding, with very little forethought or study, and done in offtime by a random non-expert, over thousands of games and tens of thousands of moves.

Indeed more skilled cheaters circumvent Chess.com anticheat in a similar fashion by just playing few engine moves at critical moments and playing their own moves the rest of the time. What’s shown here is a totally automated version of this which does not require anyone to interact with the chessboard and requires zero skill at chess.

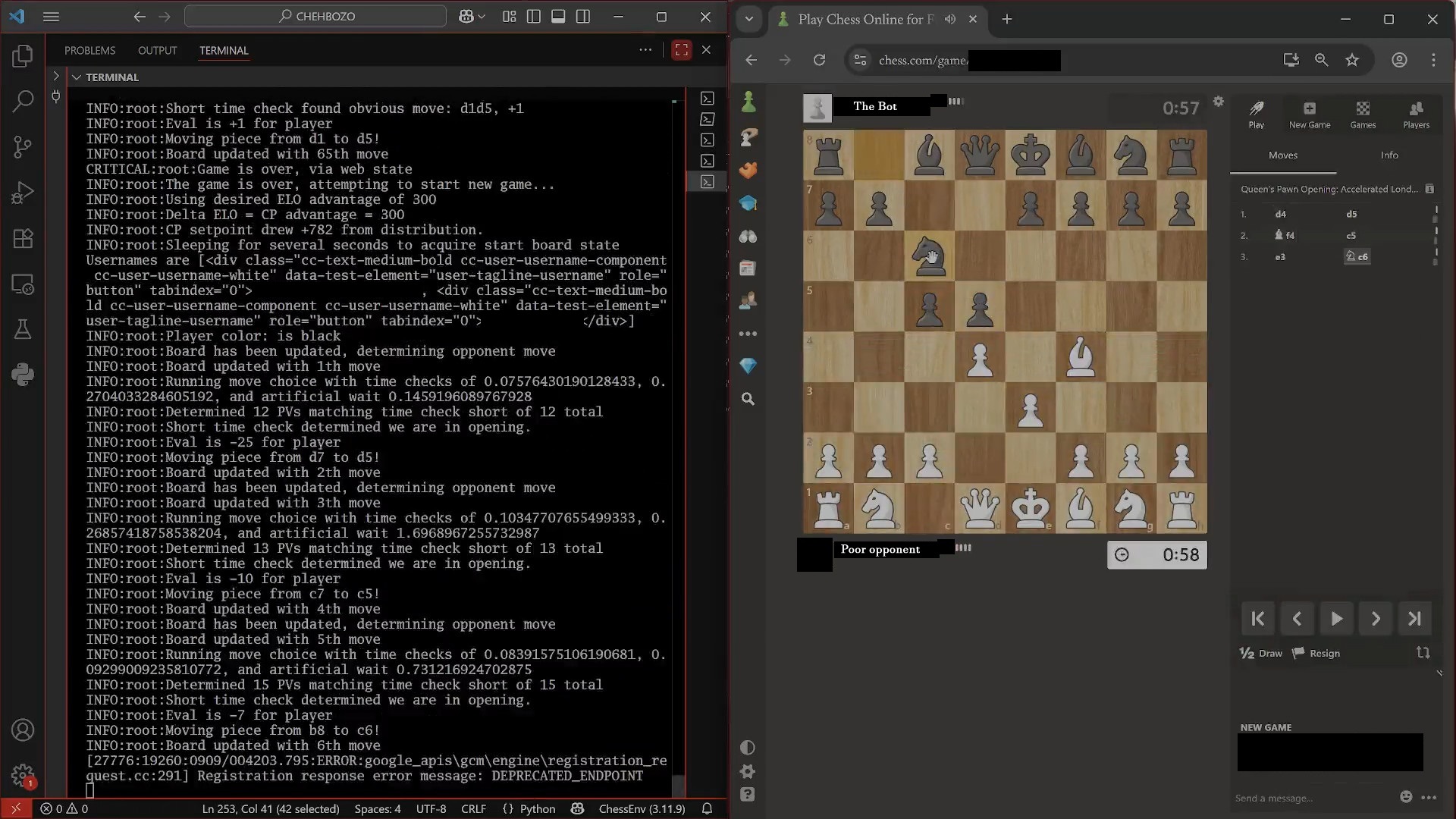

Broad strokes of how it works (technically)

This program parses the HTML of the chess.com webpage to determine the state of the game, then uses mouse automation and a custom move selection algorithm to move pieces “like a human” in selection, timing, and mouse movement. The program wins at a specified rate, without playing too many suspicious moves, and plays a specified number of games (like 500+) totally autonomously. It literally never plays a move chosen by a real human being.

Yet, it still can fly under the radar of Chess.com’s cheat detection while crushing human opponents.

More Details

The chess.com URL is launched in a browser.

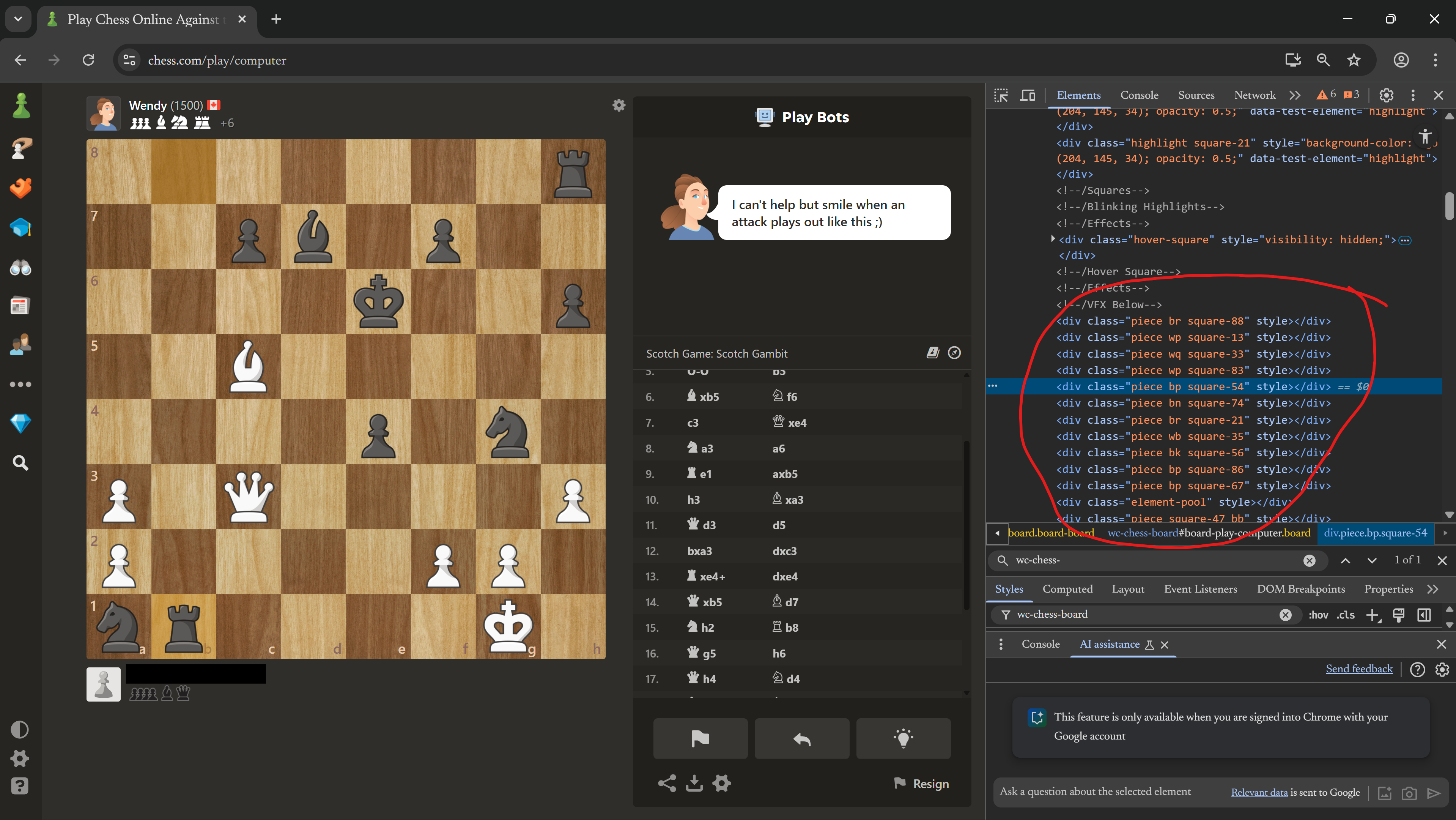

Everything about the state of the game is simply in the HTML. A webdriver (Selenium) with python bindings is able to retrieve the live HTML from the board, and coupled with BeautifulSoup and the python-chess package, we can construct the entire board state at any time. The pieces and their positions are encoded in near-plain English in the HTML (piece bp square-54 means white pawn is on e4). We can also read info such as the opponent’s name and the time remaining for each player.

A GUI automation tool pyAutoGUI simulates human mouse movements, including positional randomness, timing, mouse curve, speed, and acceleration. The mouse mover starts a new game. The screen position of the board geometry is calculated based on pixel positions, giving us a mapping of screen pixel 2-tuples (where we will send the cursor) to squares. We parse the board, players, and clock times to determine the player color based on the player’s relative tag location in the HTML. We run the chess engine and move selection algorithm to determine the next move, and pyAutoGUI moves the piece in the browser window. When the HTML updates with the opponent move, we repeat.

We play until the game is either won or lost (including the ability to resign the game if it is dead lost), and start a new game, all automated with mouse movements and clicks.

The entire psuedocode of each loop inside a game is something like this:

Automating Mouse Movements

This is probably pretty extra and did not need to be done, but just in case Chess.com is monitoring mouse movements like many sites do for tracking , the program moves the mouse to mimic imprecise-yet-smooth human mouse movements rather than pixel-precise straight lines or instant jumps.

Creating mouse trajectories

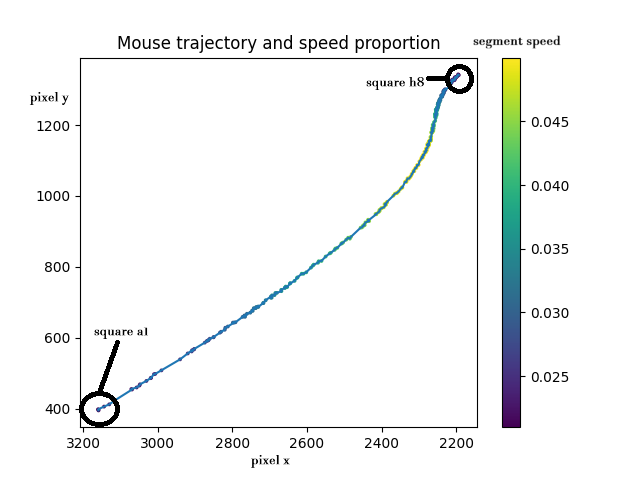

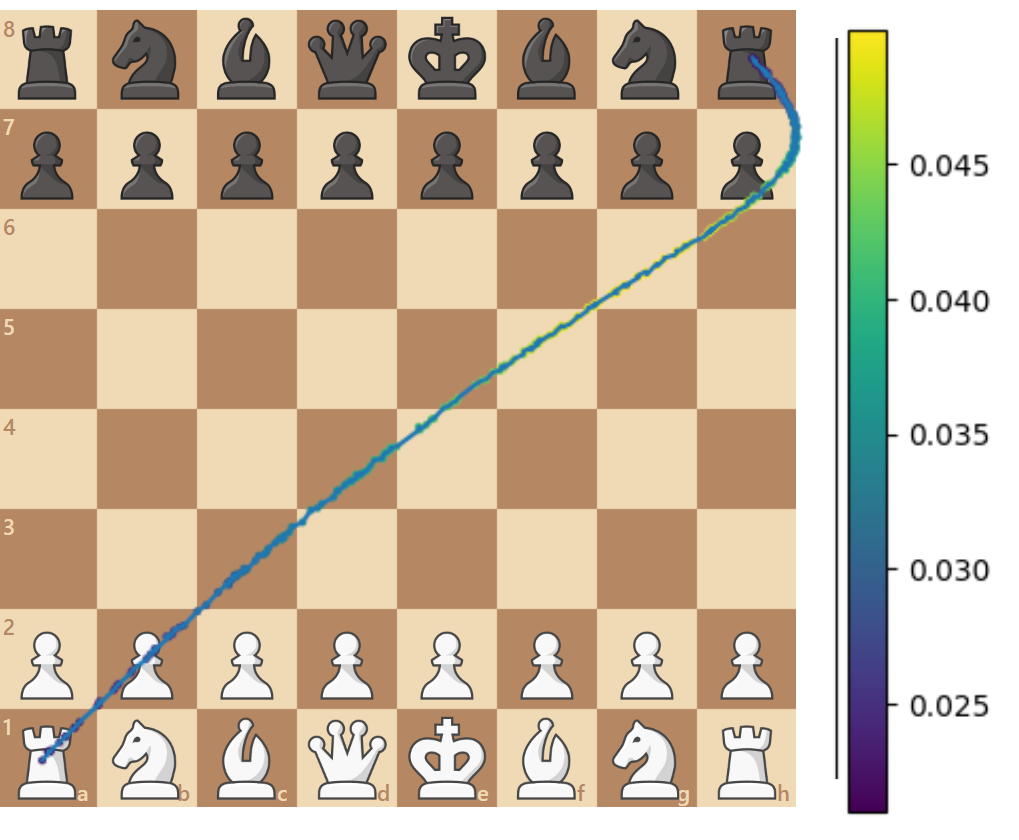

We have a mapping of all 64 Board Squares to Pixel Positions like computed automatically from only the extrema locations of either pair of terminuses of the board (a1/h8 or a8/h1). I did that literally by just using a program called MPos to see what the pixel value was for the board when aligned in a specific orientation on my screen, justified right and halfscreen with page zoom 80% and Chess.com board max-sized. Now we merely need to generate mouse trajectories given a 2-tuple of squares such as . The exact pixel positions of each square are perturbed by a few (random) pixel offsets first, so we aren’t landing on exactly the same pixels each time we go to/from a square.

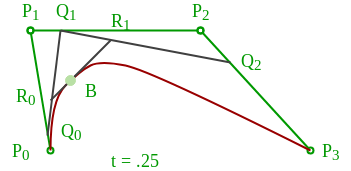

We generate noisy Bezier curves simulating a human mouse movement to give us some number points between the origin and terminus.

Now we generate linear segments between each point, since pyAutoGUI can technically only move in straight lines. Then it will run over each segment approximating a smooth trajectory.

The trajectory is made of segments :

Each segment has start and end coordinates and the time for traversal like this:

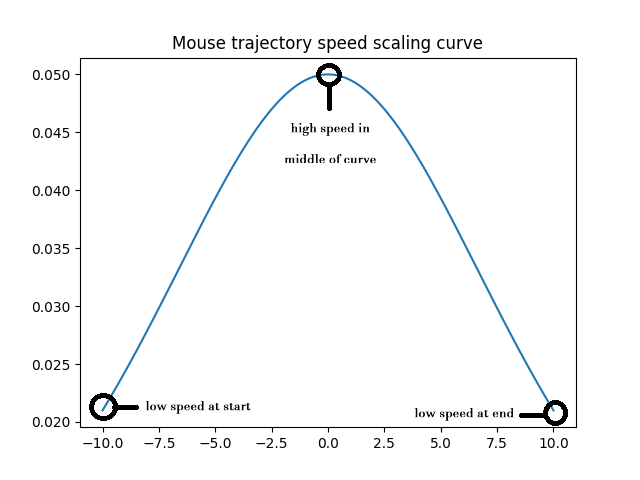

The start coordinates for a segment are the end coordinates from the previous segment: . The times are generated by first drawing a total movement time from a Gaussian distribution, dividing that up into segment times, and normalizing each of those segment times by scaling them

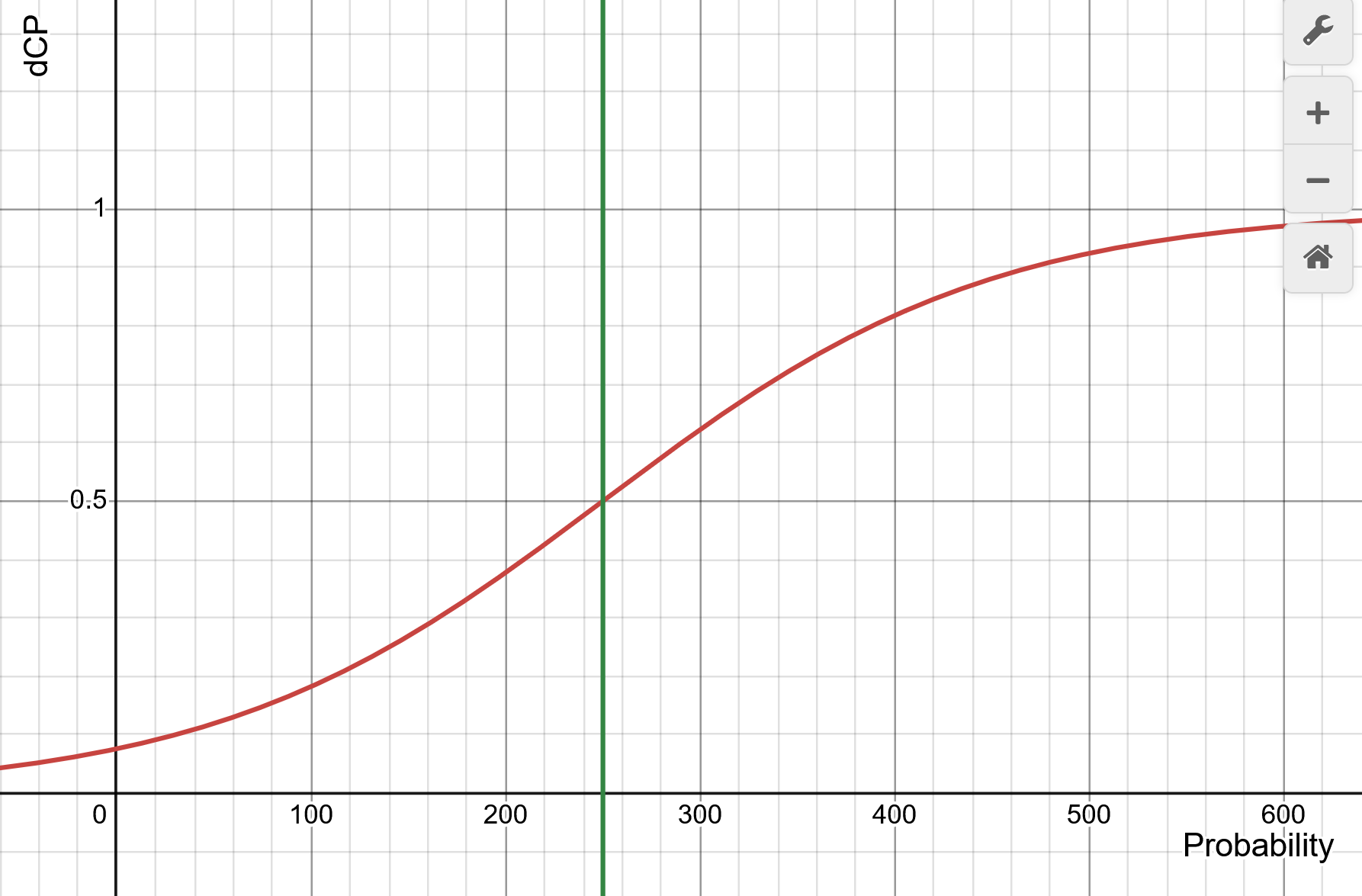

- proportionally to Euclidean segment distance, so longer segments take longer

- inversely by the derivative of a sigmoid , simulating the speed of a human accelerating and decelerating the mouse along the curve.

-

The final mouse movements

The result of all of this is a bunch of segments and times that can be passed to pyAutoGUI. When it runs, it looks pretty much like a human moving the mouse from one location to another. And it is good enough for fucking around on a chess website.

The Move Selection Algorithm

The goals of the algorithm are generally just common sense:

- Essentially, play like a good but goofy human player, more or less.

- Openings and obvious moves (like queen recaptures) should be played fast and reliably like human players do

- Extremely complex positional play or deep tactics should be few and far between. Subtle blunders by opponents (like a pawn move weakening an endgame structure 50 moves in the future) should be capitalized on sparingly.

- Occasionally, blunders should be made.

- Put opponents under time pressure when their clocks run low.

- Do not rescue dead-lost positions with insanely accurate play (a common cheater tactic) or sabotage dead-won positions with transparently intentional blunders. Resign lost games and consistently win won games.

- Avoid tunnel-visioning on outrageously difficult to see Mate-In-5+ tactics requiring huge sacrifices or bizarre-looking moves.

- Moves should be of generally consistent quality, all while not violating any of the above, and reflecting the current Elo rating of the bot.

- Win games around a low rate, like 55-60%.

- Prevent too high correlation with engine lines at any point. Especially(!) when playing other cheaters.

- Try not to arouse suspicion from human players since too many reports will bring increased scrutiny. So moves should be eye-test plausible at any given point.

Unfortunately this is actually kind of hard

Having a chess bot play suboptimal moves while both not losing the game outright and not correlating too strongly with the top lines of the engine is actually kind of difficult. It’s like balancing on a highline. Why? I could go on forever about this, but it arises from one question:

When PRECISELY do we follow a top engine line, or not?

Simply avoiding engine correlation by never or rarely playing the top engine moves will lose nearly every single game. That’s because a lot of moves in chess, like capturing back a rook in an equal exchange, are just obvious. And if that kind of blunder happens two or three times in every game, not to mention every single move, the disadvantage to the bot will be too great. Lose both rooks and a queen every game, and not even full-strength Stockfish running on a supercomputer can rescue you from losing. The bot will simply lose every single goddamned game. Conversely, play a top engine move too often and it’s the easiest way to get caught.

Further, top engine moves are lines, not individual moves. So playing a sacrifice ending in Mate-In-3 (”M3” for short) doesn’t work if your next necessary tempo is wasted on a completely unrelated pawn advance. Playing individual moves out of the engine lines at random (such as via a “frequency of top move” parameter) won’t work for this reason. Now we are starting to get complicated. So you’re telling me I can’t play the best moves, but I also can’t NOT play the best moves? Yes. We need to both play best moves and non-best moves judiciously with some sort of algorithm.

One solution is to train an AI on millions of human games to mimic human behavior like Maia does. That’s a lot of work, even for a group of dedicated academic experts. Maia also only can play up to around 1900 Elo, which is sort of a low threshold.

The good news is that we can condense all the above goals of the algorithm into a pretty simple guiding strategy.

Algorithm strategy: Analogy of a weak PID controller

My bot uses a loose, human-readable heuristic strategy:

Keep the game in the range it naturally evolves into.

A solution, sort of, from distributions of PVs:

I decided to use just what the engine gives us:

- The lines (also known as principal variations or PVs)

- Their evaluations ( numbers or Mate-In-X reflecting advantage of black/white, such as -1.4 or M7)

- And CRITICALLY, the distribution of evaluations and the depths/level of branching at which they’re found.

The algorithm’s strategy works by looking at the distribution of evaluations, the strength (via engine depth/nodes) of those evaluations, and playing moves just strong enough to win and too weak to trigger the fair-play algorithm.

The bot generally tries to keep the game around a setpoint evaluation

More or less this means the bot acts as a weak Proportional-Integral-Derivative controller (not technically but in spirit), keeping the game around a setpoint evaluation if possible, and otherwise allowing the opponent to dictate the game - either by winning or losing.

In practice, this setpoint strategy optimizes (weakly) two tradeoffs:

- Play the maximum number of top engine lines you can get away with, without getting caught

- Play the minimum number of top engine lines needed to win more often than not.

This allows the bot to lose to opponents that are playing way above their level or who are cheating, while winning on average. It either lets opponents forge their own downfall through their own blunders or by grinding them down with non-losing moves outside of the top (say 3) engine lines. It does not force a result either way. It also means we can play a huge proportion of suboptimal (unsuspicious) moves while retaining a winning advantage, but still greedily take opportunities to play top engine moves most humans would play while not triggering the fair play algorithm.

Setpoint advantage for each game is normally distributed . The mean and std. setpoint advantage in centipawns, abbrev. “CP” (terrible acronym I know), for a set of games (e.g., , AKA +3.5 in Chess.com notation) is pre-set. The setpoint advantage for a single game is drawn from this distribution, so some games will have +300CP setpoint, while others will have -50CP. Setpoint also correlates approximately with winning chances as per this sigmoidal formula , though I found other parameters had a much greater effect on winning percentage than the setpoint number.

The bot uses engine results of different strengths to gain more information on the “difficulty” of moves

The bot uses PVs and evals from the engine after working for different amounts of time, each generating a large number (10+) of PVs by running on many threads. It does not often check engine depth/nodes outright, but mostly uses computation time as a proxy.

- Short time evaluations (

short): Approximation of an “easy”/low depth engine given after running Stockfish for a short time. Since the engine does not run for long, most of these PVs are acceptable but their evaluations are slightly off. A top-rankedshortPV may actually just be a middling move.

- Long time evaluations (

long): For “hard” or higher depth moves and more accurate evaluations, if needed. An improvement overshortafter running for some additional time. The top-rankedlongPVs are strong enough to annihilate most human opponents, even in blitz/bullet, and their evaluations are quite accurate.

Both short and long return a big list of updated PVs, each with the sequence of moves, evaluation, engine parameters (such as depth of the PV) and time taken to arrive at the final eval.

We can say the PVs from short are typically more “obvious” or “natural” as they’re from a lower fidelity version of the engine than long . A PV found in short but not long is likely just a bad move, like hanging a pawn. A PV found in both short and long is probably an obvious move, like recapturing a bishop, or is at least acceptable. A PV found in long but not short is probably a more complex move, like a deep tactic. A legal move neither in short nor long is probably just trash, an outright blunder, or a complete nothingburger move.

The bot has a menagerie of common functions to filter PVs

Whether we are getting a list of PVs from short or long or both, we need some functions to go from a big list of PVs to a single selected one. These functions are:

FindBestPV: Simply return the PV with the best given evaluation

FindObviousPV: Return best PV with a probability scaled by its improvement over all other lines. Otherwise, return nothing. PVs with a vastly higher eval than the runner(s) up will be chosen frequently. PVs close to the runner(s) up will be chosen infrequently. Probability is obtained by inputting the difference in CP eval between the top PV and next-best PV, (), into a parameterized sigmoid function: . This means bestmoves giving advantage over 2nd-best moves have 50% probability. Mates in 1- and 2- are included as obvious moves.

FindSetpointPV: Given a setpoint for this game, return the PV nearest to the setpoint. The current eval must be within a setpoint “window”, usually of the setpoint. Outside of this window, returns nothing. If the game is deadlost or deadwon for example, trying to return to the setpoint is too strong of a correction. Refuses to play the best move if it is the only move in the setpoint window; if it’s not the only move in the setpoint window, remove the best move with some preset probability. If we don’t remove it, the algorithm winds up playing a bit too many suspicious “onlymoves” saving mostly lost positions.

FindNonbestPV: Within a window typically of the current eval, find a non-best move. Typically this is outside the setpoint window but with no easy way to end the game, so we are just playing moves to bide time or survive. Selects randomly from PVs where each PVs’ probability is normalized by it’s inverse to the best move, meaning 2nd-best moves have the highest probability:

FindRandomPV: Pick a random move among the PVs. This is not quite the same as picking a random legal move, since engines prune PVs if there are more legal moves than the max PV number. But it’s essentially picking a random move.

The algorithm’s pseudocode is like this

1. Draw a centipawn advantage setpoint for the player for this game.

2. Runshortuntil time is up.shortdata will be used for quickly playing openings, obvious moves, blunders, and low-material endgames/scrambles.

- If Opening: Use

FindBestPVonshortdata.

- If Middlegame or Endgame:

- If Blunder: Once per moves, play the worst possible PV by reversing the order of

FindBestPV

- If

FindObviousPVonshortdata finds an obvious move, play it.

- If Endgame and no move found from above:

- One winning mate-line: Use

FindBestPV. Since we are inshort, it’s usually something obvious like a ladder M3.

- Multiple winning mate-lines:

FindNonbestPV. All roads will lead to Rome, it will just take a bit longer. And this gives the bot a chance to stray further from top engine lines, especially when there are multiple easy mate lines fromshort

- If all else fails, use

FindBestPV. Usually this is not a big deal to play a bit more accurately in a very simplified endgame, especially with low-accuracyshortdata.

- If no move is found, we go to the next step.

3. Runlonguntil time is up. In all these following options,longdata is used.longdata will be used ifshortdata could not find a move, typically in middlegames and more complicated positions. It is also useful for getting more accurate evaluations on positions whereshortcannot really determine anything. We always uselong, nevershort, to determine whether a game is Deadwon or Deadlost, since short can give bad evaluations frequently.

- If game is Deadlost: exit the algorithm and have the bot resign if disadvantage is more than .

- If game is Deadwon:

FindBestPVonlongdata to finish the game quickly. Typically ifshortcould not find a move our best bet is just finishing the game. This does not happen often.

- Keep the middlegame on setpoint:

FindSetpointPVis the lions share of the moves typically. We are kept inside the setpoint window with suboptimal moves until either the opponent plays a strong move beyondlong's evaluation horizon (rare) or they blunder the game away (common).

- If no setpoint moves found, by the time we get here it means we are outside the setpoint window or unable to stay there, there are no obvious moves, we are in the middlegame and are neither Deadwon nor Deadlost; likely, we are losing but not yet Deadlost so we can wait with

FindNonbestPVonlongdata and see if the opponent makes a blunder.

- Finally, if everything else fails, just

FindBestPVand wait a few seconds to simulate thinking.

4. Return and make the move.

Engine thinking times for short and long are normally distributed with a lower cutoff. Sets of parameters for blitz and bullet differ but generally a short time of around 0.1s (s) and long around 0.7s () with a minimum cutoff of 0.1-0.05s is adequate for blitz and bullet. These differing runtimes of the engine add some stochastic noise to the predictions and allow the engine to differ a bit more from normal stockfish. Or that could be complete BS as I’ve never tested that, it just seemed like a good idea to randomize the thinking times a bit. Artificial wait times are also added before moves are made (20% chance) and are also randomly distributed, typically with something like , .

The end result from an anticheat perspective are move timings that look pretty human for short-time control games: 0.8s, 1.4s, 0.5s, 20s, etc.

The algorithm could be made significantly stronger by thinking on the opponent’s time, but as of right now it only thinks when it is its own turn.

If you’re thinking this is unnecessarily complicated, you’re probably right

Keep in mind I literally just spammed this shit out over a couple of weekends. To be frank, I didn’t think such a messy and shitty algorithm would be able to both win games and avoid detection, but it did both with very little fiddling.

So how does it do?

Overall, I’d say the bot plays human-ish depending on level and such. I’m around 1600-1800 on all time controls across both Chess.com, so I can’t say for sure how suspicious some moves are to a human being at higher levels. Most of the time, it wouldn’t arouse a human’s suspicion until getting around 2200+ level. It’s biggest apparent flaw is that it will extend games with winning positions to go on… for …. so… damn… long, occasionally not capitalizing on the tactic it had made a previous move for just so it can keep the game around the setpoint.

On average, maybe a few moves of an average game the bot plays between 1000-2000 would be suspicious to a human.

More importantly though, it is not detectable to Chess.com automated anticheat around these levels, or even significantly higher. The automated anticheat screening is (I’d estimate) how the vast, vast majority of cheaters get caught.

Example games of the algorithm

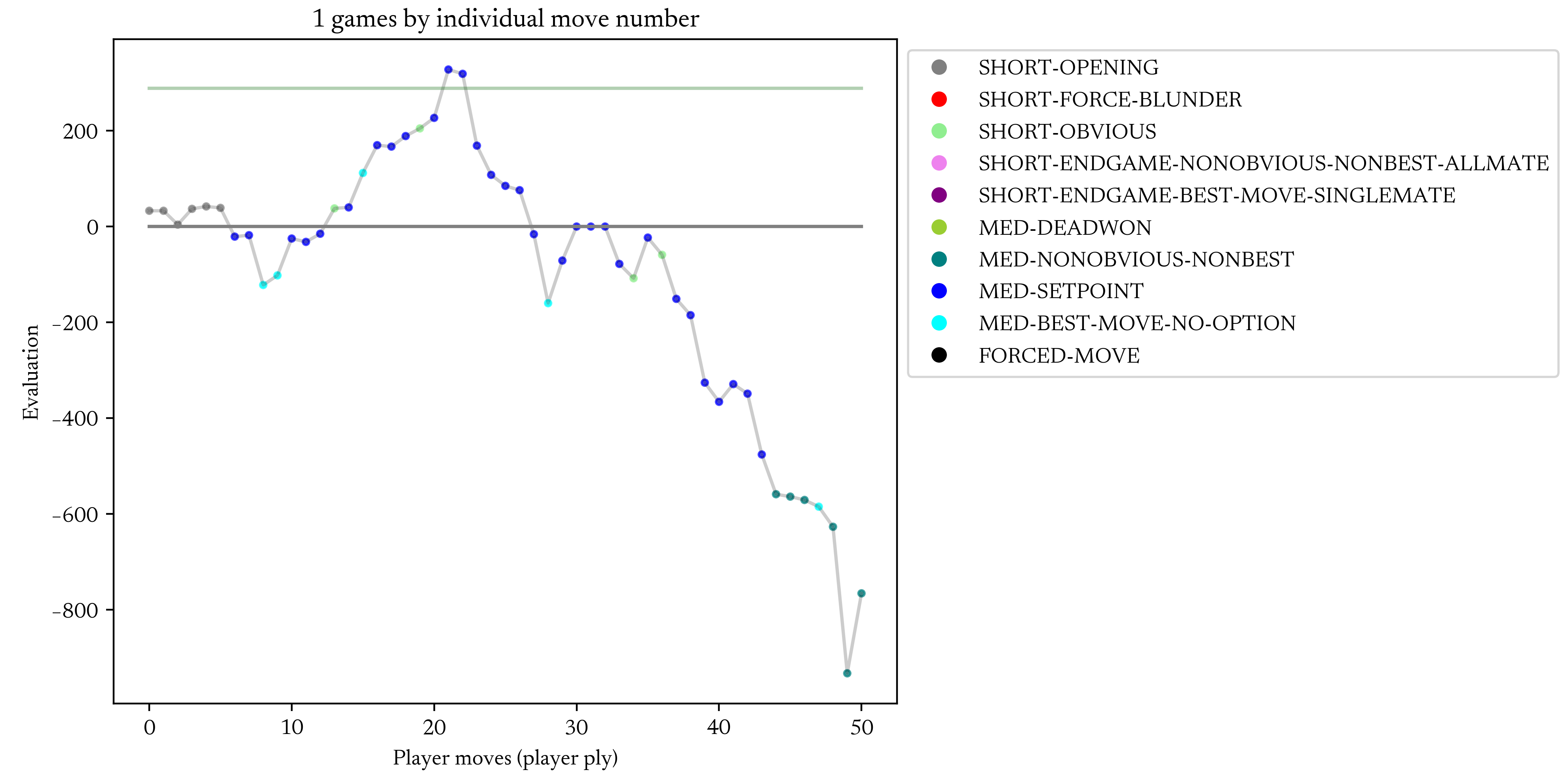

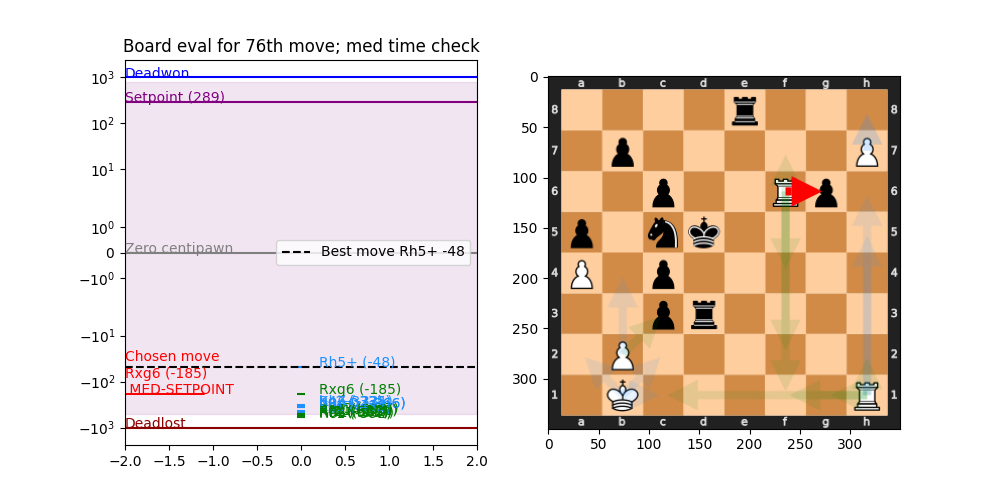

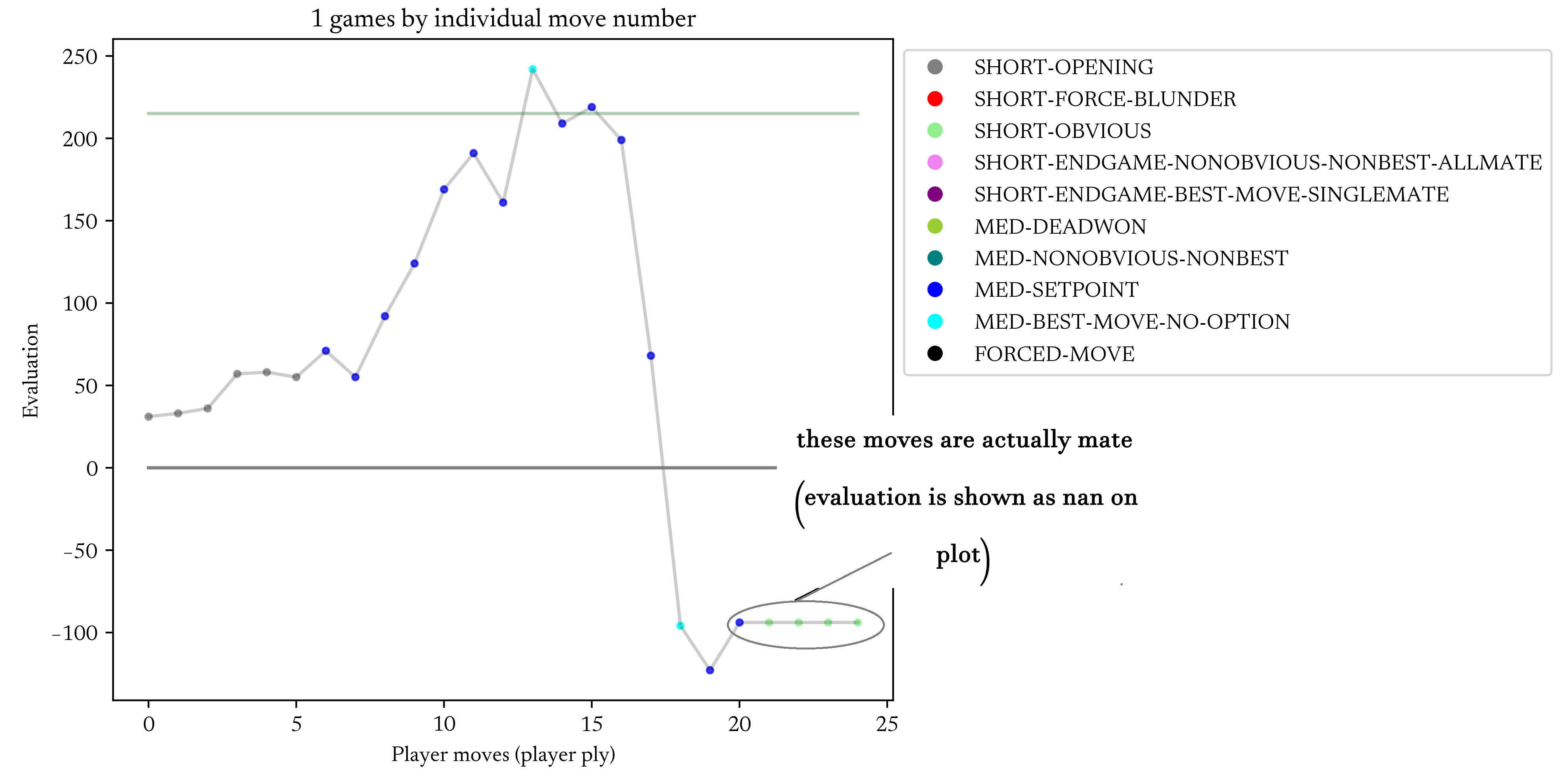

Here’s the bot playing the 2000-rated bot Li with blitz parameters and setpoint around , though the game is technically untimed. Li is a very strong opponent, especially in short time controls. In the first game, Li plays pretty good and we lose. In the second, we play until Li makes and obvious mistake and we crush it with a simple M4-like tactic. In the game evaluation plots we show the move choice reasons and evaluations used by the engine. The evaluation is always given from the player’s perspective (relative CP) and may be given by the short or long engine evals, meaning the quality of the evaluations fluctuates and does not reflect the true evaluation.

Game 1:

long due to a refactoring screw-up. “SHORT” means short engine was used for a move.

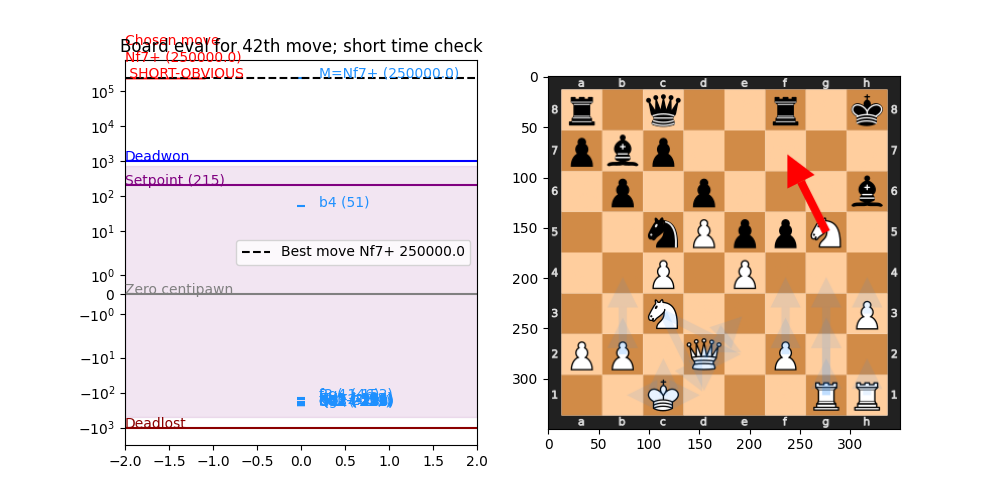

short engine moves while green is long engine moves. The full solid lines are the deadwon, deadlost, and setpoint CP. The chosen move is shown on the far left. The blue move evals are not accurate (”best move” line/text in meaningless here) bc. it was computed from the short engine in a complicated middlegame. Bh5+ is actually a poor move when looked at by long. “MED” means long.We are using the long engine, and we choose the setpoint move which happens to be the actual best move in this scenario for white Rxg6. All of our moves are still losing, however.Game 2:

nan evaluations on this plot as I didn’t convert them, but in reality Li hung an obvious mate line.

short engine (blue) and decides to play it. Although the short evals are not always accurate, they are able to find “obvious” tactics like this with regularity.

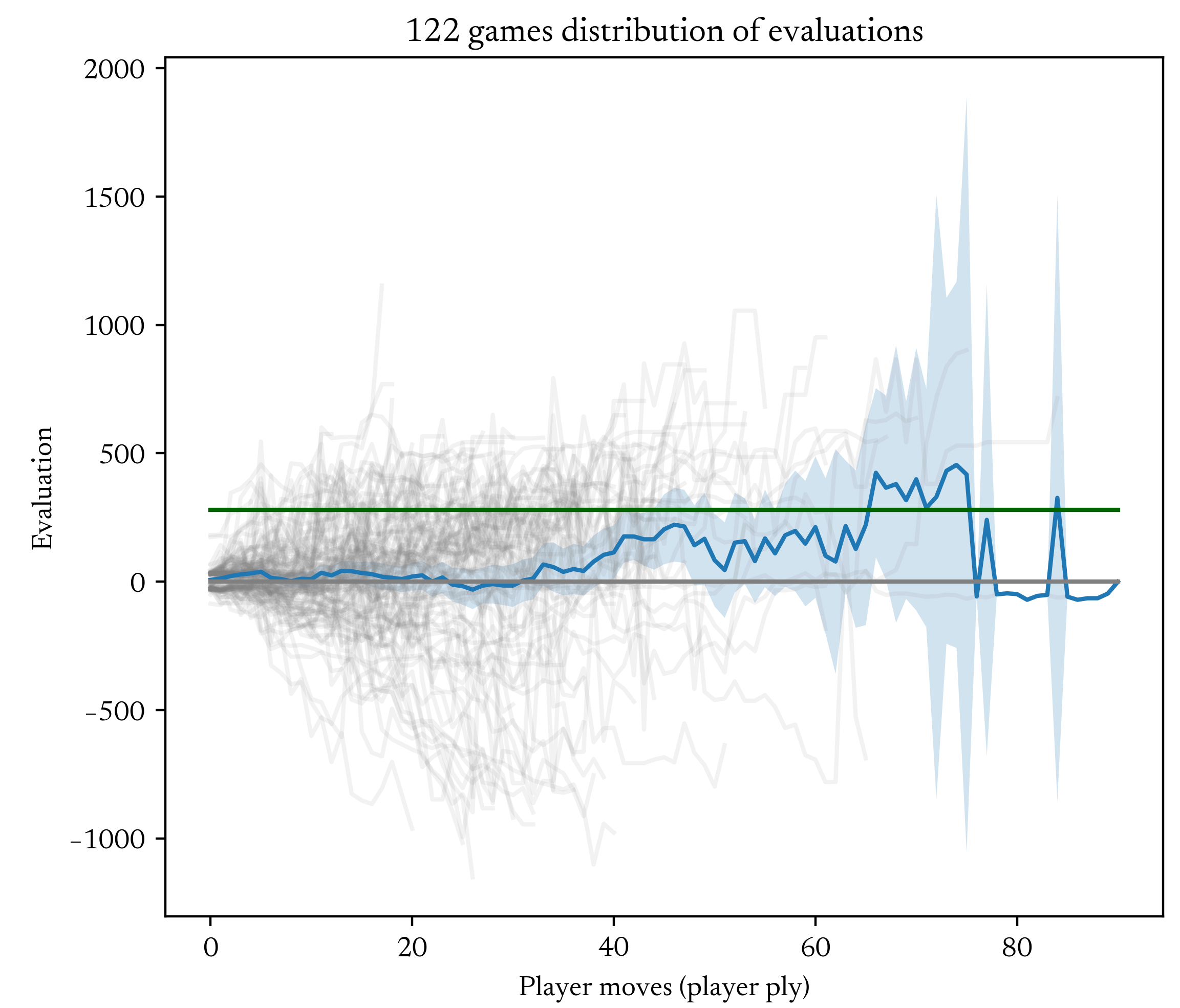

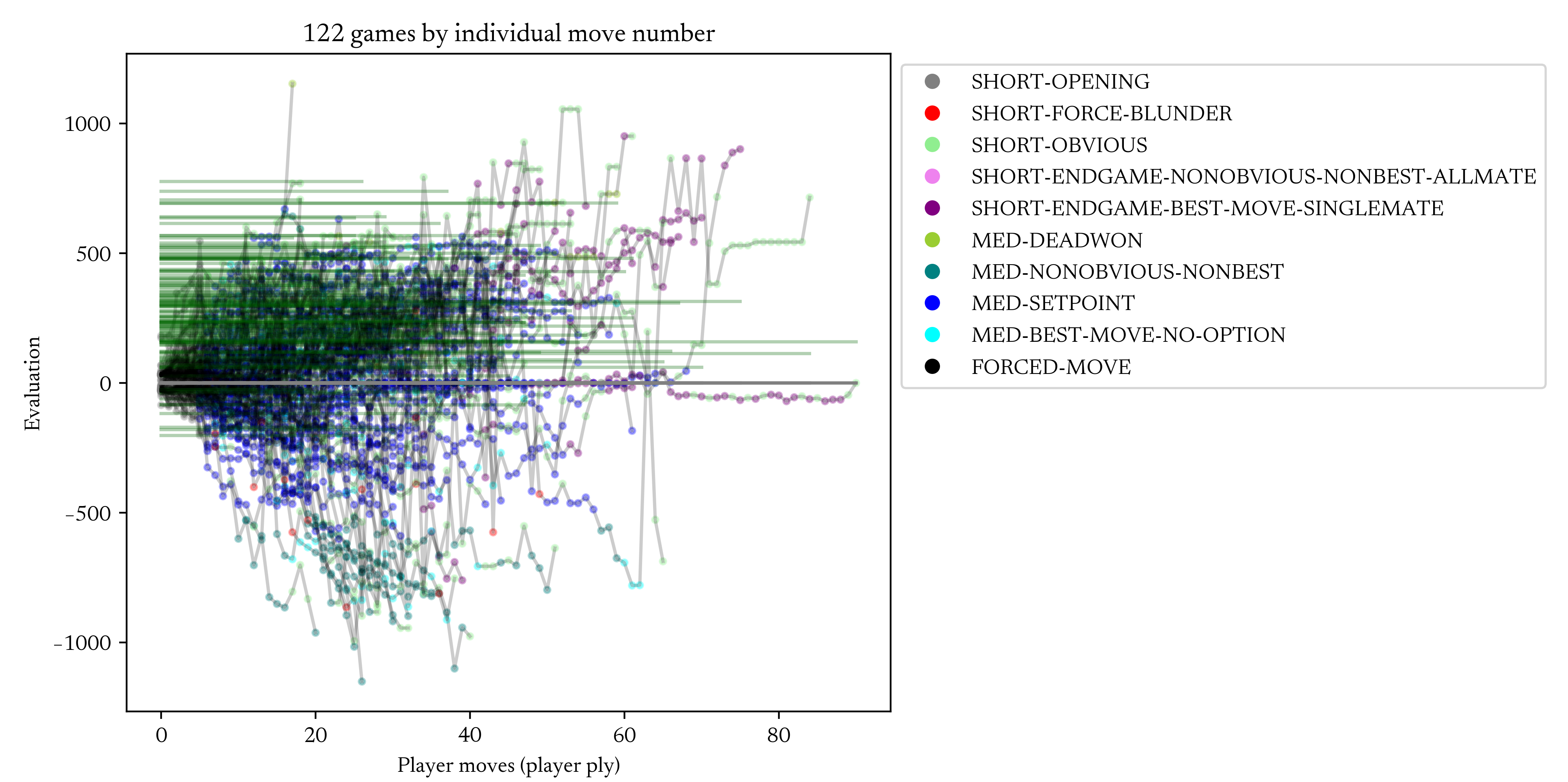

Looking at 122 blitz games of the bot against live opponents rated 2300+ using a CP setpoint of gives us this plot of evaluation vs. player ply move with the individual move choices shown for each move. Although its a poor approximation for strength, the mean Chess.com CAPS score of these games was 84% while Chess.com estimates the CAPS score for an OTB 2100 player (rapid, but correlated very approx. 2300 Chess.com blitz) is approximately 91%. So the bot is actually playing significantly less accurately than its opponents around a >2300 level while still winning 55%+ of its games.

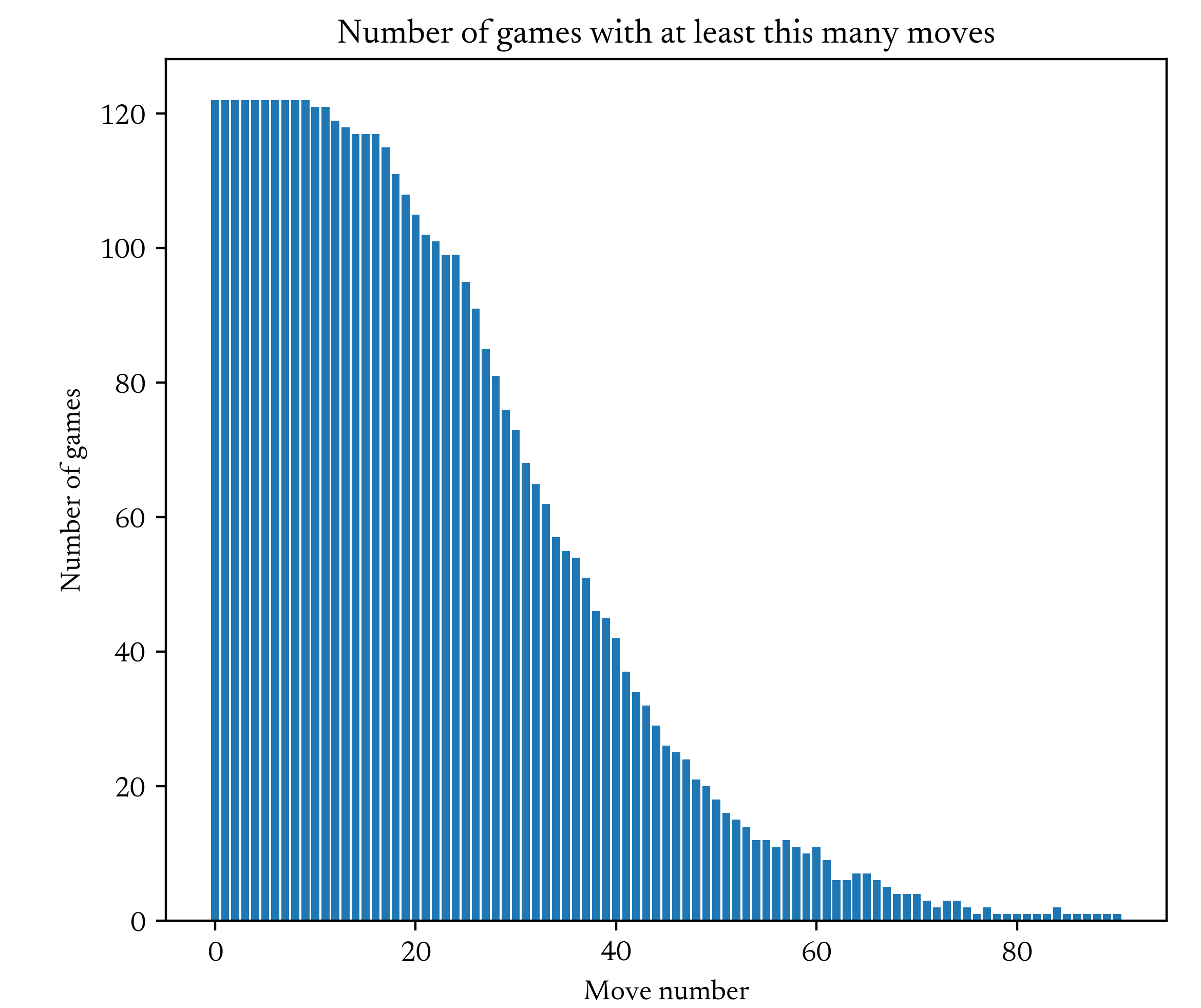

long and short calculations meaning the eval is noisy and not “true”, but overall it’s a good approximation for how these 122 games went against master-level opponents.Playing over 1,000 games

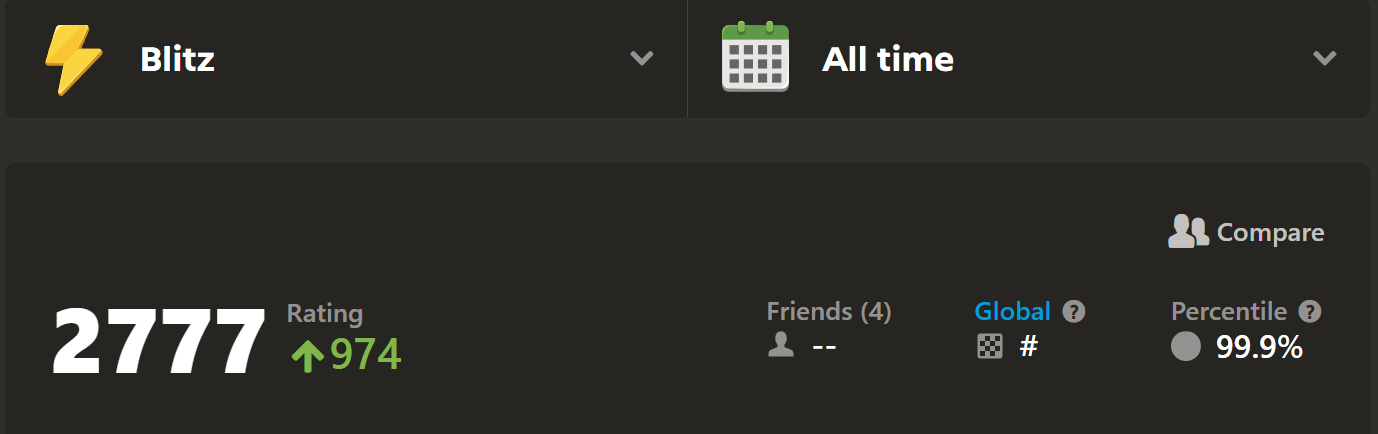

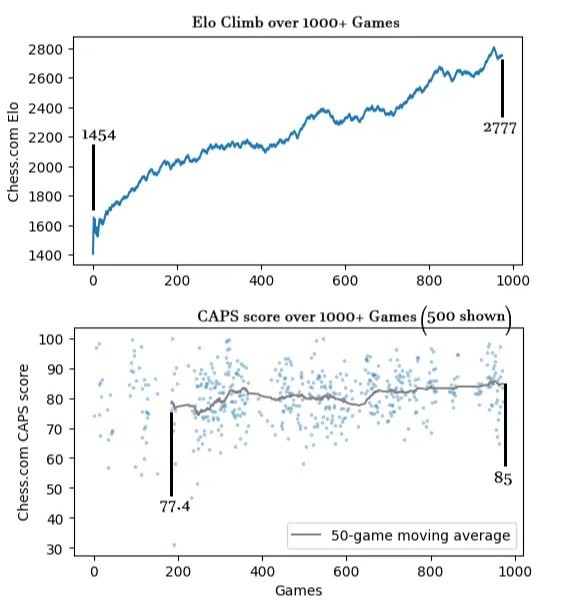

The bot climbed from approximately 1450 blitz rating to the top 1,000 in the world over a period of several months, improving average CAPS score from 77 to 85.

It made over 40,000 moves completely autonomously. This graph is comprised of multiple versions of the bot as the first (many) versions were very fucky. Especially around 2000 Elo I had to make some adjustments to the game parameters. However after 2100 Elo, the bot played essentially on its own until 2700+ with zero tuning or corrections. The CAPS score improvement was generally a result of simply playing more skilled players, as the bot will “play up” to the level of the opponent slightly.

The bot also played around 200 bullet games (rating 1350 → 2390) though I did not focus on this as much. In practice I found the bot to be much stronger from a flagging perspective in bullet games so long as it was playing 1|1 and not 1|0. In 1|0, human opponents can take advantage of the bot’s tendency to draw out long games and flag the bot beyond a certain Elo of around 2000.

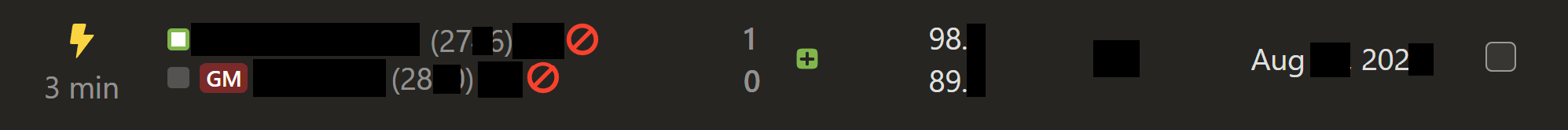

Here’s a summary of the bot’s accomplishments. Numbers have been slightly altered to mitigate forensics.

| Time Control | Start Elo | End Elo | Games | Moves |

| Blitz (3|0) | 1454 | 2777 | 1091 | 36k |

| Bullet (1|0/1|1) | 1350 | 2390 | 228 | 8k |

The downfall of the bot

The bot did eventually get caught because of these reasons three, all of which cascaded together to get it banned.

1. In the final bot version, I typo’d a parameter.

The parameter for removing best moves from FindSetpointPV is called P_REMOVE_GREATMOVE, typically around 0.6-0.9. If this parameter is set to 0, allowing all best moves to be selected for FindSetpointPV, the bot will repeatedly fall into losing positions and then repeatedly find “only moves” or “great moves” (best moves where all other moves lost the game on the spot) to save the game over and over. This leads to a much higher engine correlation than desired, hence the parameter P_REMOVE_GREATMOVE is removes greatmoves from FindSetpointPV with some probability.

In the final version of the bot, I mistyped and did not notice the parameter was set to 0.1 instead of 0.7 as intended, leading to potentially much higher engine correlations than desired.

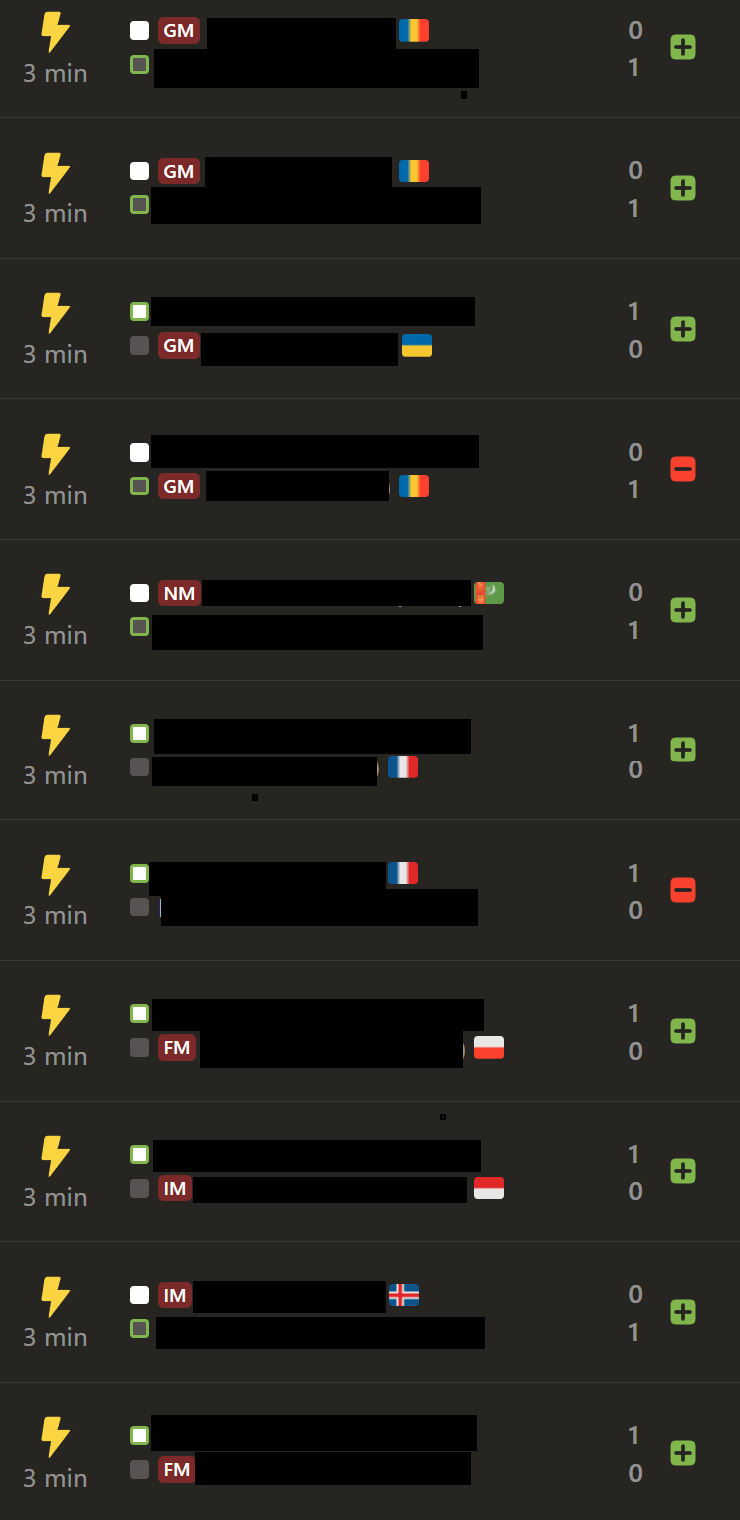

2. It played several other cheaters.

The bot eventually played a 2800-level player and, with it’s inadvertently altered code, ran up a 98% accuracy against their 89% accuracy. However that player was also cheating, and was banned! And they were a Grandmaster with the title flair! Incredible that Chess.com has so many cheaters, even among the ranks of titled and verified players. But I guess we have known that since 2022 when the Hans Niemann scandal broke.

As a cheat-bot, playing against other cheaters is very dangerous from a detection point of view. A cheater playing high-accuracy moves can force the position into extremely sharp or complicated lines where humans would otherwise be totally lost, but engines will play confident tactical moves to save advantage. In combination with the P_REMOVE_GREATMOVE parameter being set way too low, the bot played at WAY too high accuracy and engine correlation for this game and several others, mostly against cheaters.

3. The bot garnered too many reports from high-level/titled players

Suspicious Elo improvement gives away the bot:

Rage-cheaters easily get to 2000+ Elo before they are caught, they usually ascend extremely fast by winning every game, then get banned within a few games once they start playing titled players. So their rise to power is quick but short-lived.

On the other hand, the bot rose to high Elo over the course of more than 1,000 games. But this rise was still meteoric compared to legit players. Anyone looking at the Elo improvement graph for the bot would be assured it is a cheating player.

I didn’t really plan out a long term plan for slow Elo improvement, sort of just winged the whole thing. I really should have just let the bot improve slowly over like 3 years, slowly gaining Elo to become one of the best untitled accounts in the world. But I was hasty since this was a weekend(s) project and I wanted results now like Shamwow.

Titled players reported the bot

Chess.com denies they give preferential treatment to higher rated players, but I am almost sure they treat high Elo (esp. titled) players reports more seriously than random low-rated players. Once the bot started to get into the 2600+ range, I think experienced players can tell when they are playing a bot or a troll vs. a legit player (especially when the account is new-ish and has no titled flair). A few reports from titled players will get a new(er) account sent to the in-depth review of the Fair Play team.

Some hilarity along the way

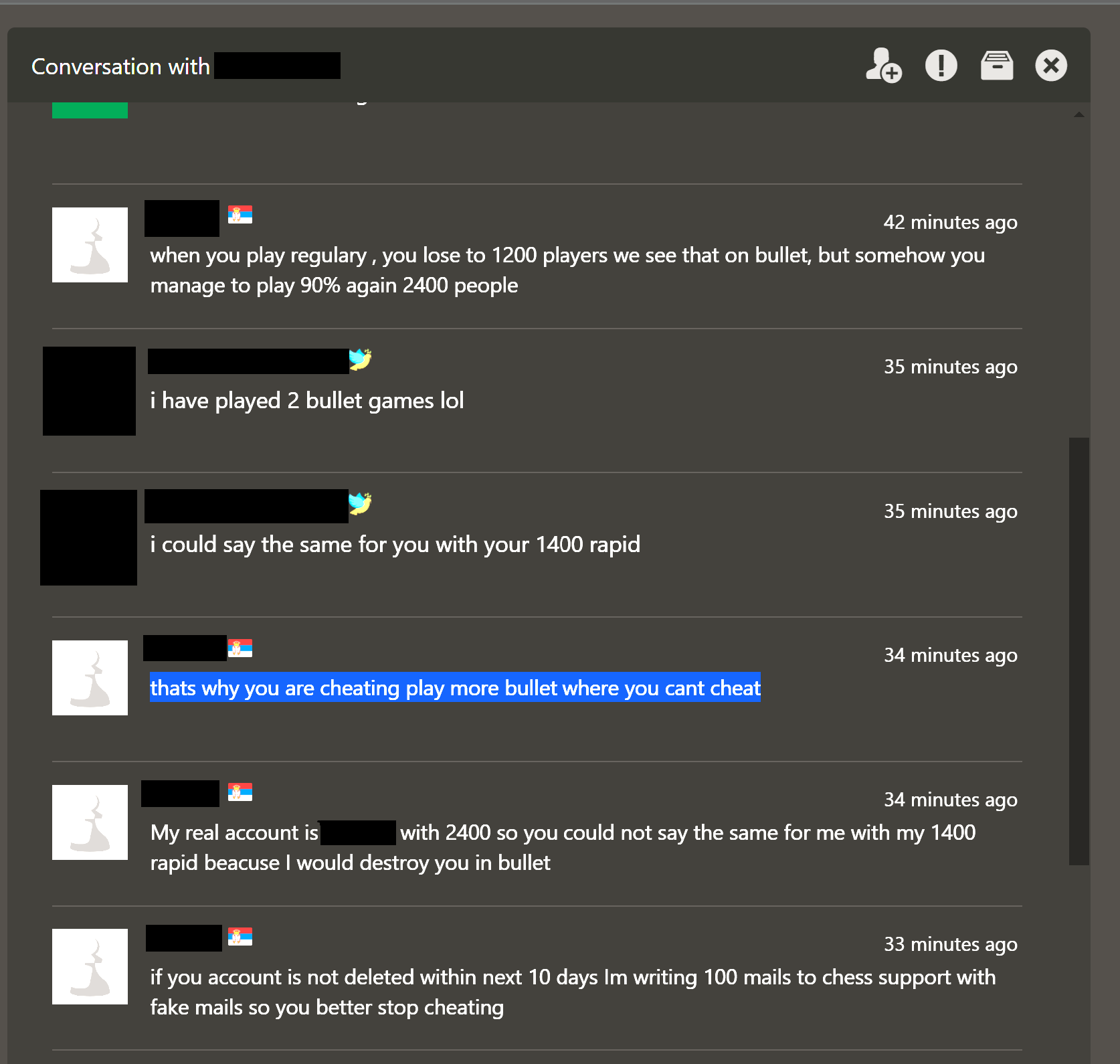

One high-rated player went out of their way to message me after the bot beat them 6-3 in 9 games. They definitely were onto me!

And then their accounts got banned both for cheating and abuse. Is every single motherfucker on this website cheating?

Around the 1200 Elo range, the bot played A LOT of cheaters in a row. In an extreme bout of irony, and doing something I have never seen before EVER, Chess.com sent the bot a free 2-week Diamond membership to compensate. Utterly insane.

Closing thoughts

Will I do it again?

Realistically, given what I know now, I am pretty sure I could spin up another account and over the next 6 months ascend it into the top several hundred players without triggering a fair play detection. I am quite confident there I could have the bot play at least 10x the number of games played in this first experiment without being caught, playing 8-16 hours a day, while staying among the top 99.999th percentile virtually indefinitely.

I will probably not do this though. This experiment was kind of fun for a while but it’s not really worth doing again. It was more of a personal challenge than anything, given Chess.com thinks so highly of their anticheat.

What can we make of all of this nonsense?

Like I said above, I really did not expect this to work so easily given my inexperience with chess engines, my lack of research into the problem, my non-expertise as a chess player, the very little amount of time and planning I put into this, and the huge amount of resources Chess.com puts into their anticheat. Yet, it did, and pretty wonderfully until I screwed it up with a typo.

It really shows that basically anyone with some programming experience, even if they are not a chess player, can use engines on Chess.com with impunity to run up an automated account into one of the top accounts in the world. And all the while, never playing a single fucking move from a human being. If I were a betting man, I’d bet there are hundreds - if not thousands, or ten thousands - of similar accounts currently alive on the platform run by people smarter and/or more dedicated and/or more malignant than I am.

This experiment opened my eyes to the fact that there are likely WAY more cheaters than what JackSark found in his video on Chess.com. 11%? 33%? Likely more like 50%, depending on the rating pool you play in, and you’ll probably never even know if you’re playing one.

If you work for Chess.com and are reading this,

Disclaimer: I can easily think of some ways you can reverse engineer some of the data in this post, even with redactions, to determine the name of this hypothetical account. For legal reasons, I will say all the above data in this post is completely fabricated and any correlation with a real Chess.com account is purely coincidental. All details and results of this bot are entirely hypothetical. Now, back to business…

If you want to reach out to me to get the name of the account without that work, I’d be glad to help. I’ll even give you the full code, if that would help as well. Though improving the Chess.com anticheat was NOT ANY part of the motivation for this expertiment, I think having access to this bot’s games would give Chess.com some more data in improving their anticheat, especially against more sophisticated cheaters.

You can contact me at DahgnueBlog@Proton.me